CRS Report for Congress The Financial Action Task Force: An Overview

出处:按学科分类—政治、法律 BERKSHIREPUBLISHINGGROUP《PatternsofGlobalTerrorism1985-2005:U.S.DepartmentofStateReportswithSupplementaryDocumentsandStatistics》第131页(14607字)

James K. Jackson

Specialist in International Trade and Finance,

Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division

Summary

The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, or the 9/11 Commission, recommended that tracking terrorist financing “must remain front and center in U.S. counterterrorism efforts.”(1) As part of these efforts, the United States plays a leading role in the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF). The independent, intergovernmental policymaking body was established by the 1989 G-7 Summit in Paris as a result of growing concerns among the Summit participants about the threat posed to the international banking system by money laundering. After September 11, 2001, the body expanded its role to include identifying sources and methods of terrorist financing and adopted eight Special Recommendations on terrorist financing to track terrorists’ funds. This report provides an overview of the Task Force and of its progress to date in gaining broad international support for its Recommendations. This report will be updated as warranted by events.

The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering is comprised of 31 member countries and territories and two international organizations(2) and was organized to defivelop and promote policies to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.(3) The FATF relies on a combination of annual self-assessments and periodic mutual evaluations that are completed by a team of FATF experts to provide information and to assess the compliance of its members to the FATF guidelines. FATF has no enforcement capability, but can suspend member countries that fail to comply on a timely basis with its guidelines. The FATF is housed at the headquarters of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris and occasionally uses some OECD staff, but the FATF is not part of the OECD. The Presidency of the FATF is a one-year appointed position, currently held by Mr. Jean-Louis Fort of France. The FATF has operated under a fiveyear mandate. At the Ministerial meeting on May 14, 2004, the member countries renewed the FATF’s mandate for an unprecedented eight years.

The Mandate

When it was established in 1989, the FATF was charged with examining money laundering techniques and trends, reviewing the action which had already been taken, and setting out the measures that still needed to be taken to combat money laundering. In 1990, the FATF issued a report containing a set of Forty Recommendations, which provided a comprehensive plan of action to fight against money laundering. In 2003, the FATF adopted the second revision to its original Forty Recommendations, which now apply to money laundering and terrorist financing.(4)

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the FATF has redirected its efforts to focus on terrorist financing. On October 31, 2001, the FATF issued a new set of guidelines and a set of eight Special Recommendations on terrorist financing.(5) At that time, the FATF indicated that it had broadened its mission beyond money laundering to focus on combating terrorist financing and that it was encouraging all countries to abide by the new set of guidelines. The FATF eight Special Recommendations are:

1. Take immediate steps to ratify and implement the 1999 United Nations International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism and Security Council Resolution 1373 dealing with the prevention and suppression of the financing of terrorist acts;

2. Criminalize the financing of terrorism, terrorist acts and terrorist organizations;

3. Freeze and confiscate funds or other assets of terrorists and adopt measures which allow authorities to seize and confiscate property;

4. Report funds that are believed to be linked or related to, or are to be used for terrorism, terrorist acts, or by terrorist organizations;

5. Provide the widest possible range of assistance to other countries’ law enforcement and regulatory authorities in connection with criminal, civil enforcement, and administrative investigations;

6. Impose antimoney laundering requirements on alternative remittance systems;

7. Strengthen customer identification requirements on financial institutions for domestic and international wire transfers of funds;

8. Ensure that entities such as nonprofit organizations cannot be misused to finance terrorism.

The FATF completed a review of its mandate and proposed changes that were adopted at the May 2004 Ministerial meeting. The new mandate provides for the following five objectives: (1) continue to establish the international standards for combating money laundering and terrorist financing; (2) support global action to combat money laundering and terrorist financing, including stronger cooperation with the IMF and the World Bank; (3) increase membership in the FATF; (4) enhance relationships between FATF and regional bodies and non-member countries and; (5) intensify its study of the techniques and trends in money laundering and terrorist financing.(6)

Progress to Date

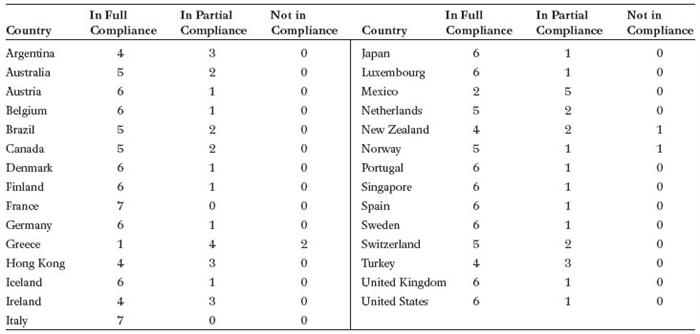

An essential part of the FATF activities is assessing the progress of its members in complying with the FATF recommendations. As previously indicated, the FATF has attempted to accomplish this activity through assessments performed annually by the individual members and through mutual evaluations. According to the 2002-2003 assessment provided by the FATF members, two countries, France and Italy, were in full compliance, as indicated in Table 1. Only three countries, Greece, New Zealand, and Norway, were in non-compliance relative to any of the recommendations. The rest of the members were in full compliance or partial compliance of seven of the eight Special Recommendations on terrorist financing. The one Special Recommendation that is not considered in the survey relates to the performance of nonprofit organizations. Part of the difficulty the FATF faces in determining how fully member countries are complying with the Special Recommendations is in reaching a mutual understanding of what the Recommendations mean and how a country should judge its performance relative to the Recommendations, since the Recommendations are periodically revised and new methodologies for analyzing money laundering and terrorist financing are adopted. In addition, a number of the Recommendations require changes in laws and other procedures that take time for member countries to implement. To assist member countries in complying with the FATF Recommendations, FATF has issued various Interpretative Notes to clarify aspects of the Recommendations and to further refine the obligations of member countries.

Between 2002 and 2003, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank participated in a year-long pilot program to conduct assessments on money laundering and terrorist financing in various countries(7) using the methodology developed by the FATF.(8) In March 2004, the IMF and World Bank agreed to make the program a permanent part of their activities. Over the year, the IMF and the Bank conducted assessments in 41 jurisdictions. According to these assessments, the Fund/Bank reached a number of conclusions regarding the overall compliance with the FATF 40 Recommendations and the eight Special Recommendations. In particular, they concluded that overall compliance was uneven across jurisdictions, but that jurisdictions display a higher level of compliance with the FATF 40 Recommendations than they do with the eight Special Recommendations due to shortcomings in domestic legislation. In general, the Fund/ Bank concluded that compliance is higher among high and middle income countries than in low income countries. The most common weaknesses identified by the IMF and the World Bank include:

■ Poor coordination among government agencies, especially among financial supervisors, financial investigators, the police, public prosecutors, and the public.

■ Ineffective law enforcement due to a lack of skills, training, or resources to investigate, prosecute, and adjudicate money laundering cases among police, prosecutors, or the courts.

Table 1 Country Self Assessments Relative to the FATF Special Recommendations on Terrorist Financing 2002-2003 (Special Recommendations 1-7)

Source: Annual Report 2002-2003, Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering, June 20, 2003. Annex C.

■ Weak supervision by financial supervisors due to understaffed or undertrained supervisors who lacked the skills or capacity to monitor and enforce compliance with money laundering or terrorist financing requirements.

■ Inadequate systems and controls among financial firms to identify and report suspicious activity, or to ensure that adequate records were being maintained.

■ Shortcomings in international cooperation due to strong secrecy provisions, restrictions placed on counterpart’s use of information and the inability to share information unfiless a criminal investigation was already underway or a formal agreement was in place.

For each of the Special Recommendations, the IMF and the World Bank offered additional conclusions:

1. Ratification and implementation of U.N. instruments. Almost one-third of the jurisdictions assessed by the IMF/ World Bank failed to comply with this recommendation.

2. Criminalizing the financing of terrorism and associated money laundering. This Recommendation was one of the least observed by the jurisdictions reviewed.

3. Freezing and confiscating terrorist assets. About one third of the jurisdictions that were assessed displayed serious deficiencies complying with this Recommendation, generally because there was a lack of explicit legal provisions or other arrangements that would require the freezing of funds or assets of terrorists.

4. Reporting suspicious transactions related to terrorism. Forty percent of the assessed jurisdictions displayed a lack of legal and institutional measures that would require making a report to competent authorities when there is a suspicion that funds are linked to terrorist financing.

5. International cooperation. This recommendation, which covers mutual assistance and extradition in financing of terrorismfirelated cases, is one of the least observed recommendations, where almost half of the relevant countries exhibited significant deficiencies.

6. Alternative remittance systems. In most jurisdictions, such remittances were judged to be irrelevant, but of those jurisdictions that were considered, one-half were found to be deficient.

7. Wire transfers. Compliance was assessed inconsistently because there was ambiguity about whether the standard was in force. Those jurisdictions that were not in compliance generally lacked formal requirements that complete information be included in each transaction.

In February 2004, the FATF adopted a revised version of the 40 Recommendations that significantly broadens the scope and detail of the Recommendations over previous versions. Also, the FATF adopted a new methodology to track and identify money laundering and terrorist financing that applies to both the 40 Recommendations and the eight Special Recommendations. As a result of the significant length and additional detail of these new requirements, the FATF decided that it will no longer conduct self-assessment exercises based on the previous method, but will initiate follow-up reports to mutual evaluations.

Issues for Congress

Following the 9/11 attacks, Congress passed P.L. 107-56 (the USA PATRIOT Act) to expand the ability of the Treasury Department to detect, track, and prosecute those involved in money laundering and terrorist financing. In 2004, the 108th Congress adopted P.L. 108458, which appropriated funds to combat financial crimes, made technical corrections to P.L. 10756, and required the Treasury Department to report on the current state of U.S. efforts to curtail the international financing of terrorism. The experience of the Fifinancial Action Task Force in tracking terrorist financing, however, indicates that there are significant national hurdles that remain to be overcome before there is a seamless fiow of information shared among nations. While progress has been made, domestic legal issues and established business practices, especially those that govern the sharing of financial information across national borders, continue to hamper efforts to track certain types of financial fiows across national borders. Continued progress likely will depend on the success of member countries in changing their domestic laws to allow for greater sharing of financial information, criminalizing certain types of activities, and improving efforts to identify and track terroristfirelated financial accounts.

The economic implications of money laundering and terrorist financing pose another set of issues that argue for gaining greater control over this type of activity. According to the IMF, money laundering accounts for between $600 billion and $1.6 trillion in economic activity annually. Money launderers exploit differences among national anti-money laundering systems and move funds into jurisdictions with weak or ineffective laws. In such cases, organized crime can become more entrenched and create a full range of macroeconomic consequences, including unpredictable changes in money demand, risk to the soundness of financial institutions and the financial system, contamination effects on legal financial transactions and increased volatility of capital fiows and exchange rates due to unprecedented cross-border transfers.(9)

Order Code RS21904, updated March 4, 2005