CRS Report for Congress The National Counterterrorism Center: Implementation Challenges and Issues f

出处:按学科分类—政治、法律 BERKSHIREPUBLISHINGGROUP《PatternsofGlobalTerrorism1985-2005:U.S.DepartmentofStateReportswithSupplementaryDocumentsandStatistics》第717页(30749字)

Todd M. Masse

Specialist in Domestic Intelligence and Counterterrorism Domestic Social Policy Division

Summary

In July 2004, the National Commission On Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States recommended the establishment of a National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) to serve as a center for “. . . joint operational planning and joint intelligence, staffed by personnel from the various agencies. . . .” On August 27, 2004, President George W. Bush signed Executive Order (EO) 13354, National Counterterrorism Center, which established the National Counterterrorism Center and stipulated roles for the NCTC and its leadership and reporting relationships between NCTC leadership and NCTC member agencies, as well as with the White House. In December 2004, Congress passed the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, P.L. 108-458. Like the preceding executive order, among many other reform initiatives, the act prescribes roles and responsibilities for the NCTC and its leadership.

The purpose of this report is to outline the commonalities and potential differences between EO 13354 and P.L. 108-458, as these conceptual differences could be meaningful in the implementation process of P.L. 108-458 and/or should the issue of intelligence reform be re-visited by the 109th Congress.The report examines some aspects of the law related to the NCTC, including the relationship between the NCTC’s Director and the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), which may have implications related to policy and implementation of an effective and efficient nationally coordinated counterterrorism function. Moreover, the report examines several issues that may be of interest to Congress as the NCTC matures and evolves, including potential civil liberties implications of collocating operational elements of the traditional foreign intelligence and domestic intelligence entities of the U.S. Intelligence Community.While the appointment and confirmation of a DNI may resolve some of the uncertainty regarding the NCTC, the NCTC is only one of a myriad of complex issues that will be competing for the time and attention of the recently nominated DNI.

An issue for Congress is whether to let the existing intelligence reform law speak for itself (and let certain ambiguities be resolved during implementation), or to intervene to address apparent ambiguities through amendments to the law now. Alternatively, the executive branch may choose to intervene to clarify apparent ambiguities within P.L. 108-458, or between EO 13354 and P.L. 108-458. In any event, congressional oversight of the status quo and implementation of the present law could prove useful.

This product will be updated as necessary.

Introduction

Currently there are two legal mechanisms governing the establishment of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC).(1) The NCTC was initially established by Executive Order 13354, signed by President George W. Bush on August 27, 2004. Section 3 of EO 13354 outlined the functions of the NCTC which included, among others, (1) serving as the primary organization within the U.S. government for analyzing and integrating all intelligence possessed by the U.S. government pertaining to terrorism and counterterrorism, (2) conducting strategic operational planning for counterterrorism activities, (3) assigning operational responsibilities to lead agencies for counterterrorism activities, and (4) serving as a shared knowledge bank on known and suspected terrorists and international terror groups. Less than two months later, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (hereinafter the act) became P.L. 108-458. Section 1021 of the act amends the National Security Act of 1947, as amended (50 U.S.C. 402 et. seq.) to establish within the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, a National Counterterrorism Center. The primary NCTC missions outlined in the act are largely consistent with those stipulated in EO 13354. However, there are some differences between these two legal mechanisms that may be worthy of congressional consideration. Moreover, within Section 1021 of the act itself there are some provisions that may prove problematic if efficient and effective implementation of a nationally coordinated counterterrorism function is to take place in a timely manner.

Executive Orders and Statutes(2)

The President’s constitutional authority to issue executive orders (EO) related to national security is derived from Article Ⅱ, Section 2, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which identifies, among other powers, that the President serves as the “. . . Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States. . . . ”(3) In general, the President can also issue executive orders based on congressionally delegated statutory authority.The preamble to EO 13354 titled, National Counterterrorism Center, states that the President’s authority to issue the executive order flows from the “. . . authority invested in (the) President as by the Constitution and laws on the United States of America, including section 103(c)(8) of the National Security Act of 1947 (as amended). . . . ”(4) At the time the executive order was issued this section of the National Security Act stipulated that the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), acting as head of the IC shall “. . . perform such other functions as the President or the National Security Council may direct.”(5)

One of the issues for the 109th Congress with respect to the implementation of the functions outlined for the NCTC, or the role and responsibilities of its Director, is the extent to which the executive order and Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (hereinafter Act) are consistent, or at least not contradictory. In general, executive orders are interpreted as having the force of law, unless they contravene existing law.(6) Given that the NCTC, its roles and responsibilities, and those of its Director, have been established in both an executive order and in statute, it is reasonable for one to conclude that any differences or inconsistencies would be resolved in favor of the statutory language.While this is true generally, given that the intelligence reform legislation passed in the 108th Congress is open to interpretation in some areas,(7) the basis for this interpretation could be either the legislative history of P.L. 108-458 or EO 13354. As a result, legislative oversight and potential amendments to the act in the 109th Congress are possible. As a means of understanding the varying conceptual underpinnings for the NCTC, its Director, and how its Director relates to the established Director of National Intelligence, it may be useful to outline the areas of commonality and difference between these two legal authorities.

Genesis of the NCTC

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, two authoritative reports concluded that the lack of adequate and timely coordination and communication within the Intelligence Community (IC) was one factor contributing to the inability of the IC to detect and prevent the terrorist attacks. The Joint Inquiry Into Intelligence Community Activities Before and After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001 (hereinafter Joint Inquiry) concluded, in part, that

Within the Intelligence Community, agencies did not adequately share relevant counterterrorism information, prior to September 11. This breakdown in communications was the result of a number of factors, including differences in agencies’ missions, legal authorities and cultures. Information was not sufficiently shared, not only between Intelligence Community agencies, but also within agencies, and between the intelligence and law enforcement agencies.(8)

While the Joint Inquiry did not recommend the creation of a National Counterterrorism Center per se, it did recommend the following measures, which are largely consistent, in a conceptual sense, with the creation of the NCTC: (1) the development, within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), of an “all-source terrorism information fusion center,” and (2) congressional consideration of legislation, modeled on the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-433), to “. . . instill the concept of “jointness” throughout the intelligence community.” With respect to the all-source terrorism information fusion center, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L.107-296) created within DHS an Information Analysis and Infrastructure Protection (IAIP) Directorate which has, among other functions, legal responsibility for the fusion of federal, state and local intelligence information to “identify and assess the nature and scope of terrorist threats to the homeland.”(9) Subsequently, in his State of the Union Address on January 28, 2003, President George W. Bush announced the creation of a new organization, the Terrorist Threat Integration Center (TTIC) designed to “. . . merge and analyze all threat information in a single location.” While the IAIP continues to exist within DHS, TTIC and its fusion functions have been absorbed into the newly-created NCTC Directorate of Intelligence.(10)

Like the Joint Inquiry, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (hereinafter The Commission) also found, among other factors,(11) that the lack of information sharing and coordination within the IC led to numerous missed operational opportunities(12) to detect and prevent the attacks. However, it also expounded on the virtues of “jointness” with respect to operational planning, unification of effort, and analysis. Seeking “unity of effort across the foreign domestic divide” and deliberate avoidance of the proliferation of intelligence “fusion” centers, one of the Commission’s central recommendations was the creation of an NCTC which would have responsibilities for both joint counterterrorism operational planning, and joint intelligence analysis.(13)The central tenets of this recommendation were incorporated into both EO 13354 and P.L. 108-458, albeit in somewhat different forms.

Commonalities Between EO 13354 Approach and P.L. 108-458(14)

There is a high degree of consistency between section three of EO 13354 “Functions of the Center,” and the “Primary Missions” provisions of P.L. 108-458.(15) Under each of these legal mechanisms, the NCTC is to (1) be the primary organization for analysis and integration for “. . . all intelligence possessed or acquired by the United States Government pertaining to terrorism and counterterrorism . . .”(16) (2) conduct strategic operational planning for counterterrorism activities, “integrating all instruments of national power, including diplomatic, financial, military, intelligence, homeland security, and law enforcement activities . . .” within and among agencies; (3) assign operational responsibilities to lead departments or agencies, as appropriate, with the limitation that the Center “. . . shall not direct the execution” of operations; (4) serve as a “shared knowledge bank on known and suspected terrorists and international terror groups, as well as their goals, strategies, capabilities, and networks of contact and support;” and (5) ensure that agencies “. . . have access to and receive” allsource intelligence “needed to execute their counterterrorism plans, or perform independent, alternative analysis.”

Potential Inconsistencies Between EO 13354 Approach and P.L. 108-458

It is clear that at least with respect to the baseline functions of the NCTC, there is general agreement between the executive and legislative branches of government. However, as it pertains to the roles and responsibilities of the Director of the NCTC, who has yet to be named, and reporting relationships for the Director of the NCTC to the DNI and to the President, there is less agreement between these two legal mechanisms. The executive order specifies how the President prefers to implement the functions of the NCTC. However, the act altered some of the processes and structures underlying the executive order. While the explicit Act will take precedence legally, ambiguities in implementation may cause confusion, which could undermine the intent of integrating the counterterrorism function nationally.

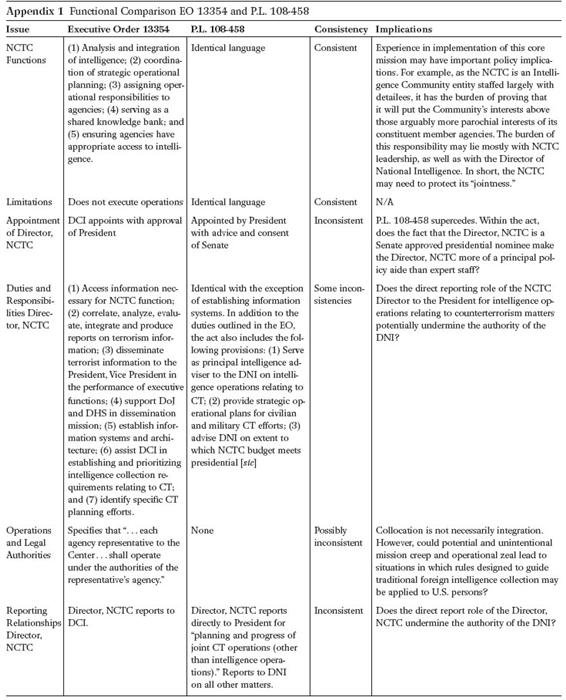

There are at least two areas in which there are inconsistencies between the executive order and the act: (1) the appointment of the Director of the NCTC, and (2) the roles and responsibilities of the Director of the NCTC, including the reporting relationships associated with this position. Appendix 1 outlines some of the potential inconsistencies or factors which may complicate effective implementation of the NCTC’s mission between the executive order and the act, and within the act itself, which may be of congressional interest. To the extent that there are inconsistencies or contradictions between these two legal mechanisms specific provisions of the act would take precedence over the executive order.

NCTC Director Appointment.

First, with respect to the appointment of the Director of the NCTC, the executive order stipulates that this individual will be appointed by the DCI with the approval of the President. As a result of P.L. 108-458, however, the position of DCI, as envisioned in the National Security Act of 1947, as amended, no longer exists.(17) Under the act, the Director of the NCTC is appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. Although the NCTC now has an acting director, former head of the TTIC, John O. Brennan, it is not known at this time whether he will be asked by the President to assume the statutorily defined role of Director of the NCTC. It is possible that the nomination of the Director of the NCTC may not occur unless and until the U.S. Senate confirms Ambassador John Negroponte, the President’s nominee for DNI.

NCTC Director Reporting Relationships

Second, a possibly more stark contradiction exists between the executive order and the act with respect to the reporting relationships for the Director of the NCTC. Under the executive order, the reporting chain of command for the Director of the NCTC would have the individual reporting directly to the DCI who, in turn, would report to the President. Even if one changed the language in the executive order—replacing DCI with DNI—a substantial difference between the executive order and the act in the reporting relationships of the Director of the NCTC would remain. Under the executive order, the DCI would have “. . . authority, direction, and control over the Center and the Director of the Center.” In contrast, the act has the Director of the NCTC’s reporting responsibilities bifurcated. According to P.L. 108-458, the Director of the NCTC reports to the DNI with respect to (1) budget and programs of the NCTC, (2) activities of the NCTC’s Directorate of Intelligence, and (3) the conduct of intelligence operations implemented by other elements of the IC. However, according to the act, the Director of the NCTC also reports directly to the President with respect to the “. . . (other than intelligence operations).”

Issues for Congress

The differences between the executive order and Act are summarized here only to highlight alternative perspectives with regard to the NCTC. Should Congress consider amending P.L. 108-458, it may want to examine elements within the act that may contribute to a lack of clarity within the NCTC and the broader IC.While clarity can be a byproduct of experience, specific guidance may prove useful in facilitating the more rapid development of effective and efficient operations.

There are at least two areas within Section 1021 of P.L. 108-458 that may be worthy of additional congressional scrutiny. The first concerns the bifurcated reporting relationships the act outlines for the Director of the NCTC.Through this mechanism the Director of the NCTC reports directly to President with regard to “the planning and progress of joint counterterrorism operations (other than intelligence operations).” This language could be construed to mean that under the act the Director of the NCTC will be reporting to the President on the planning and progress of joint military counterterrorism operations, a role traditionally reserved to components of the Department of Defense (DOD). As noted earlier, the Director of the NCTC also reports to the DNI with respect to (1) the budget and programs of the NCTC; (2) the activities of the NCTC’s Directorate of Intelligence; and (3) the conduct of intelligence operations implemented by other elements of the IC. The act, then, differentiates between joint counterterrorism “intelligence operations” and other (presumably military) counterterrorism operations.This bifurcated structure was intentionally designed to reflect what the Commission and the Congress believed should be the dual missions of the NCTC. Its first mission is to integrate and analyze all counterterrorism intelligence available to U.S. government departments and agencies and to serve as a knowledge bank on known and suspected terrorist and international terrorist groups. Given that this function is directly germane and limited to intelligence-related activities, the act stipulates that the Directorate of Intelligence report to the DNI. It is the second function—strategic counterterrorism operational planning—that gave rise to the unique reporting structure that has the Director of the NCTC reporting directly to the President for planning and progress of joint counterterrorism operations. According to Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, a cosponsor of the act and the ranking member of the then named Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, the strategic operational planning function is an “. . . an Executive branch wide planning—which is beyond the DNI’s jurisdiction.” (18)

While such reporting mechanisms and processes may be necessary to achieve “jointness,” it is not implausible to foresee potential conflicts between the DNI and the Director of the NCTC concerning who is the President’s primary advisor with respect to joint counterterrorism operational initiatives. Is the role of the DNI as “. . . principal adviser to the President, to the National Security Council, and the Homeland Security Council for intelligence matters relating to national security . . .”(19) undermined by establishing a separate reporting channel to the President for certain counterterrorism operations? Moreover, given that the Director of the NCTC is a confirmed Presidential appointee, a question could be raised as to whether the individual will serve more of a policy advisory role to implement the Administration’s agenda, or will serve as an unbiased professional civil servant.(20) Some believe, however, that the NCTC Director will have greater analytical independence and objectivity because the incumbent will be confirmed by the Senate.(21)

A second issue which may be of interest to appropriate congressional oversight committees is the collocation of what has traditionally been foreign and domestic intelligence operators. In general, national security professionals look favorably upon the concept of “jointness,”(22) at least in part as a result of the positive results yielded from the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986.This favorable predisposition generally extends to the intelligence arena, especially with respect to joint intelligence analysis projects. Alternative analysis, “red teaming,” and competing analysis conducted creatively and without undue duplication, are all generally thought to result in better analysis. However, with respect to joint intelligence operations and the integration of traditionally foreign and domestic intelligence operations, there seems to be less of a consensus. At a macro level, it is clear that coordination(23) in intelligence operations is a common good. Yet, the legal mechanisms and regulations that underlie and guide foreign intelligence collection and domestic intelligence collection, particularly as it relates to U.S. persons,(24) are substantially different.(25)

The act defines strategic operational planning as “. . . the mission, objectives to be achieved, tasks to be performed, interagency coordination of activities, and the assignment of roles and responsibilities.”(26)The executive order does not directly define strategic operational planning, other than to state generally that it involves the integration of all instruments of national power. As stated above, under both the executive order and the act, the NCTC itself is expressly prohibited from executing operations; it assigns roles and monitors overall counterterrorism operational progress. It is explicitly stated in the executive order that “. . . each agency representative to the Center, unless otherwise specified by the DCI, shall operate under the authorities of the representative’s agency.” That is, while strategic planning may be joint, if the NCTC Director assigns the FBI, CIA, and Department of Defense certain counterterrorism operational responsibilities, each agency operates under its own legal authorities. While it may be implicit, no such similar and explicit legal authority guidance was provided in P.L. 108-458.

The FBI has physically moved a substantial portion of its operational and analytical counterterrorism personnel from FBI Headquarters to offsite locations in the interest of closer coordination with the rest of the IC’s counterterrorism entities. (27) While not necessarily “integrated” into the NCTC, these individuals are now “collocated” with elements of the NCTC. As envisioned by the Commission and P.L. 108-458, this collocation could yield substantial analytical dividends, particularly when information systems are integrated in a manner that allows for closer analytical collaboration across the IC.The collocation of IC personnel engaged in counterterrorism operations may also lead to substantially improved and informed counterterrorism operations. Human assets recruited by the IC can be highly mobile. As these individuals move between the United States and overseas locations, coordination amongst and between IC agencies having sole or shared jurisdiction can add substantial value to an operation, and avoid inefficient as well as potentially embarrassing operational overlaps. Recent media coverage suggests tension between the FBI and the domestic intelligence arm of the CIA on domestic intelligence activities.(28)While a distinction must be made between collocation, which implies reliance on existing legal authorities, and integration, which implies the creation of a new body of law and regulations, the possibility exists that unintentional mission creep and operational zeal could lead to situations in which rules designed to guide traditional foreign intelligence collection may be applied to U.S. persons.That is, the civil liberties of U.S. persons could be at risk if domestic intelligence collection is directed against them in a manner that may not be consistent with or constrained by appropriate Attorney General Guidelines.(29)

Finally, with respect to the resolution of disputes between the NCTC and its constituent agencies, the act stipulates that the DNI shall resolve conflicts. In the event that the heads of constituent agencies disagree with the DNI’s resolution, they may appeal the resolution to the President. Given the NCTC’s role to “. . . monitor the implementation of strategic operational plans,” it is possible to envision conflicts between the NCTC and an agency with respect to what exactly constitutes “implementation” and how, specifically, operational success is defined. This may be exacerbated by the act’s distinction between joint intelligence counterterrorism operations, and joint counterterrorism operations other than intelligence. Regardless, resolution of potential disputes within the NCTC is one area that may be worthy of congressional oversight.

Options for Congressional

Consideration

An issue for Congress is whether to let the existing intelligence reform act speak for itself (and let certain ambiguities be resolved during implementation), or to intervene to address apparent ambiguities through amendments to the act now. Alternatively, the Executive Branch may choose to intervene to clarify apparent ambiguities within P.L. 108-458 or between EO 13354 and P.L. 108-458.(30) In any event, congressional oversight of the status quo and implementation of the present act could prove useful.

Should Congress amend intelligence reform legislation in the 109th Congress, or introduce new legislation (possibly through the annual intelligence authorization process) related to the NCTC, there are at least two areas in which it might consider action.The first concerns the reporting relationships of the Director of the NCTC to the DNI and to the President. While the coordination of planning for counterterrorism operations is necessarily an executive branch wide endeavor, the daily implementation of such practice remains a relatively nebulous function and may, therefore, be a topic for close congressional oversight. Some might argue that if a close professional and personal bond develops between the President and the DNI,(31) then a direct reporting chain for the Director of the NCTC to the President for certain joint operations relating to counterterrorism is unlikely to undermine the DNI’s new authority. The frequency, substance, and duration of the direct meetings between the President and theDirector of the NCTC may pale in comparison to those between the President and the DNI.However, it is possible that confusion could develop because the act differentiates between intelligence joint counterterrorism operations and joint counterterrorism operations (other than intelligence operations)—presumably military operations. This distinction may prove difficult to make in practice because, generally, even joint military counterterrorism operations require sound tactical intelligence to achieve their objectives.

Second, Congress may wish to consider adding to its expressed prohibition for the NCTC to execute operations, language which would explicitly clarify the legal authorities of constituent NCTC members with respect to counterterrorism operations. Alternatively, Congress could consider specifically stating in law that the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board established in P.L. 108-458,(32) has explicit responsibility for oversight of the joint counterterrorism operations of the NCTC, particularly when these operations involve U.S. persons.

Finally, another potential area for congressional scrutiny may be the appropriate arrangements and congressional committees that have jurisdiction over the activities of the NCTC.While the Directorate of Intelligence’s activities are largely bounded by traditional intelligence functions, such as the setting of collections requirements, collection of raw intelligence, and the conduct of intelligence analysis, the Directorate of Strategic Operational Planning’s activities go beyond intelligence. As such, the universe of committees having oversight over the executive branch wide functions associated with strategic operational planning may exceed those that will conduct oversight over the NCTC’s Directorate of Intelligence. One could envision a situation in which, not unlike the activities of the Department of Homeland Security, the number of committees claiming jurisdiction over the NCTC’s Director of Strategic Operational Planning could be substantial. The challenge would then be to coordinate congressional oversight in a manner that is rigorous and meaningful without unduly burdening NCTC leadership.

Conclusion

The ostensible purpose for the creation of intelligence “centers,” including the NCTC, is to bring together the disparate elements of the IC having different intelligence foci and missions in order to achieve common intelligence and national security objectives. Given the positive results of “jointness” achieved in the armed forces context as a result of the Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, there is an inherent attraction to apply such “best practices” to the IC.Yet the cohesive integration of functions across the IC requires relatively clear guidance, or at least the absence of contradictory or confusing authorities. With respect to the NCTC, the act outlines some authorities which may cause a lack of clarity,which may, in turn, undermine the effective and efficient implementation of a truly national approach to counterterrorism. The bifurcated reporting relationships the act outlines for the Director of the NCTC, ill-defined distinctions between joint counterterrorism intelligence operations and joint counterterrorism operations (other than intelligence), as well as the authority of the NCTC to define operational success and have the tools necessary to ensure compliance with its joint plans, are all areas in which unclear authority could lead to inefficient business practices. Professionalism, and a high degree of commitment among the counterterrorism cadre assigned to the NCTC, may go a long way toward ameliorating these ambiguities and thus negate the need for legislative action. It is also possible, however, that the ambiguities outlined in the act may only complicate the inevitable growing pains associated with establishing an effective, nationally coordinated counterterrorism intelligence effort.

As such, narrowly targeted and clarifying oversight guidance or legislative remedies may assist the NCTC in reaching optimal effectiveness in the least amount of time.

Order Code RL32816, Updated March 24, 2005